A 14 month year old boy has a fever for the past 4 days. The fever peaked at 38.5°C as measured at home. The child has been irritable and clingy since arriving at the GPs, but has not shown any obvious pain. There is no photophobia, neck stiffness or rash. There has been a non-productive cough for two days, which is worse at night. There is no history suggesting stridor, respiratory distress or wheeze. He has had a runny nose over this time. He is tolerating food and drink, although he is eating less than normal. He sometimes vomits after eating. There have been no changes to his bowel habits and he is producing about 6 wet nappies a day.

Examination is difficult. He cries at the slightest intrusion of his personal space by anyone other than his mother. His temperature is 37.2, although mum tells you he just had calpol about thirty minutes ago. His pulse is 120. There is subcostal and intercostal recession when he is crying, but none when the crying settles. His respiratory rate when he is settled is 40. His saturations are 96% on air. The anterior fontanelle is neither bulging nor sunken.

An ENT examination is almost impossible. You eventually find it to be normal. There is no rash top to toe. His chest sounds clear. His abdomen is soft.

You go to write up your findings to give yourself time to think whilst mum dresses the child. You have not found the source for the fever. You look at the PMH – he was a preterm baby at 34/40 weeks but has been generally well since. His development has been fine. All his vaccinations have been up to date. He is an only child, and no household contacts have been unwell.

But it’s only a ‘fever’ of 37.2 – that’s not significant

You only have a snapshot of the child’s temperature. You cannot discount the parental concerns about fever over the past four days based on a one-off reading just now. NICE state:

“Reported parental perception of a fever should be considered valid and taken seriously by healthcare professionals”

Then it’s a feverish child with no source! Admit, admit!

There are basically two things that mean a feverish child may need admission –a) suspicion of a serious bacterial infection or b) not coping with the illness itself e.g. dehydration, first ever/complex febrile convulsion, respiratory distress etc.

Regarding a) – the majority (>80-90%) of fevers in children will be self-limiting viral infections.

Regarding b) – the majority of children will cope absolutely fine with a febrile illness.

Our task is to identify the minority who have a problem with a) or b) for further assessment. We should advise the remainder to self-care at home with safety netting. Sometimes you cannot quite 100% pin down the source; this in itself does not necessarily require an urgent assessment.

How do you interpret the fever in light of the fact that the child took calpol?

It does not matter. The height of the fever in a child over 6 months does not predict a serious bacterial infection, nor does it tell you how the child is coping with the illness. The height of the fever is therefore not going to alter your management plan.

In infants less than 3 months, a fever greater than 38°C should be seen urgently by a paediatrician (red flag in NICE guidelines).

In infants between 3 and 6 months, a fever greater than 39°C is an amber flag in NICE guidelines.

Isn’t it great that NICE guidelines are perfect! We don’t have to think, just use the table!

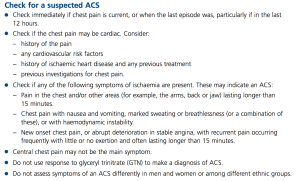

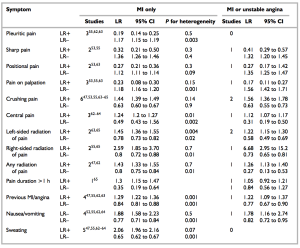

The traffic light system is helpful. It does not replace clinical judgment. This reflects the fact it is difficult (?impossible) to create a rigid scoring system for something as complex and nuanced as assessing a feverish children. The most common bacterial infection the traffic light system misses is a UTI – in fact, about one fifth of the time a child with a UTI will score green. There has been a suggestion to add urinalysis to the NICE traffic light assessment of the feverish child (http://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f866). However, there are also some who feel that this study considered only the traffic light system in isolation, without considering the NICE guideline’s holistically. The purpose of the traffic light system was not to diagnose but to help with the initial triage of feverish children. (http://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g2056/rr/691345)

So what is this magical table?

Have a look: traffic light system for identifying risk of serious illness

The main thing to emphasise is that NICE states that if the child appears unwell to you, refer urgently. Your clinical gestalt is valuable, no matter your level of experience with children ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3458229/).

What happened in this case?

It’s a fever of unknown source. There are some suggestions of a viral source (runny nose, non productive cough) but nothing definitive. There is no way you can predict what will happen in 4, 8 or 24 hours. The mother was told to contact us if the child remained clingy/crying frequently at home. Given the child had green flags at the time of assessment, and the mother knew when to come back or when to go to A&E, the child could be watched at home with appropriate safety nets.

Cool. Alternating paracetamol and tepid sponging then to keep T < 38.

NO! That is so 2008. You treat fever only so the child doesn’t feel distressed. You do not give antipyretics to target a temperature.

And you only give ibuprofen or paracetamol (at least initially). Alternating doses leads to frequent dosing errors. If the fever is not controlled with either agent alone, and the child is distressed, then maybe you could alternate them – but ask the parents to keep a written record of what they have given and when. And forget tepid sponging. Just dress the child in clothes which are appropriate for the room temperature.

Any specific advice for the parents?

NICE CKS mentions the following:

- Look for signs of dehydration including poor urine output, dry mouth, sunken anterior fontanelle (usually closed by 18 months), absence of tears, sunken eyes, and poor overall appearance).

- Offer regular fluids (if breastfeeding, continue this as normal) and encourage a higher intake if signs of dehydration develop.

- Dress the child appropriately for their surroundings, with the aim of preventing overheating or shivering.

- Avoid using tepid sponging (using cool water) to cool the child.

- Check the child regularly, including during the night (how often depends on the situation).

- Keep the child away from nursery or school while the fever persists, and notify the nursery or school of the illness.

- Advise parents and carers to seek medical help if:

- The child is getting dehydrated.

- The child has a fit.

- The child develops a non-blanching rash.

- The fever lasts longer than 5 days.

- The child is becoming more unwell.

- They are distressed or concerned that they are unable to look after the child.